A simple guide to producing synthetic grass

- 09/16/2020

By Bryn Lee

The process to produce the fibre that is used in artificial grass is called extrusion. In very simple terms raw polymer pellets, colour and UV additives are mixed together, then transformed into either a tape or individual fibres. These are then twisted and wound onto spools that are then sent to the next stage of the production process.

Polymer

At first, synthetic turf was made from nylon (PA), then polypropylene (PP), and now mainly Polyethylene (PE). Control of this raw material is in the hands of a few major plastic producers, who control the market value of their product, occasionally creating shortages to manipulate the cost of their materials. The most common polymer used is a grade known as C4, but more advanced producers use C8 a purer, stronger material. This is more expensive, but helps to produce longer lasting yarns.

Fibrillated or monofilament

Whilst using the same raw materials, after the melting and mixing part, two different but similar production routes are followed. Fibrillated yarn is created as a tape, which has a perforation pattern added, that allows fibres to open up on tufting, to create the grass-like appearance. Below we focus on monofilament yarn.

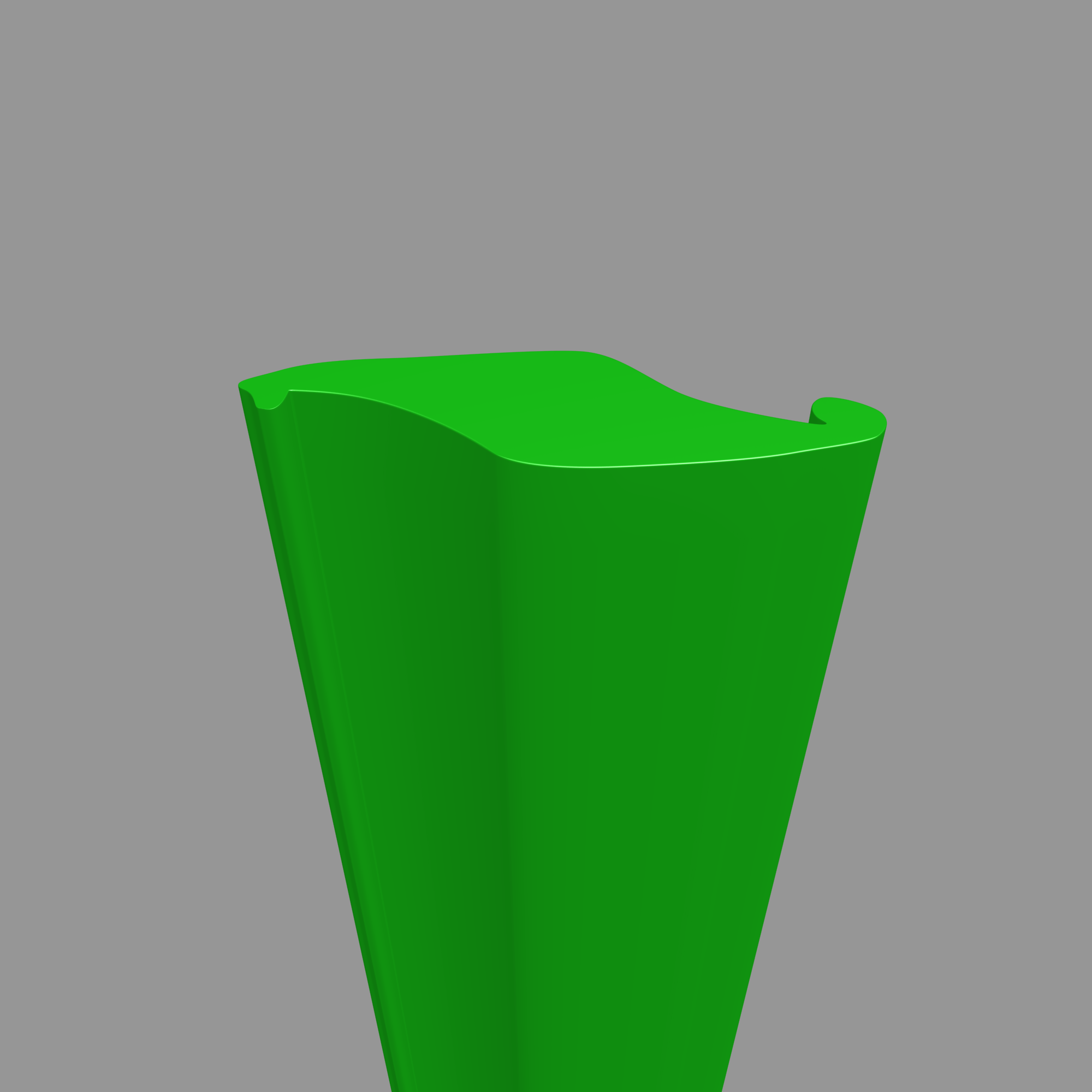

Shape

With monofilament yarn it is possible to create different shapes. This allows for creativity in design, with some shapes, such as diamond, proving more resilient and stronger than flatter yarns. The still pliant, hot, mixed material is squeezed, a little like toothpaste, through a specially created dye, into individual fibres. These are then stretched and cooled, before groups are combined together, which eventually become the tufts, in the finished turf.

Colour

Right at the beginning of the extrusion process, the master colour batch is added. This is the point where different coloured yarns can be created. Normally, a master batch will produce a specific volume of colour, enough to make several fields. However, matching the same specific green master batch to another of the same colour does not always create a perfect match.

It is possible to combine different shades of green in one tuft, to create a more natural grass appearance, with emerald, olive, lime and forest being the most common shades.

Weight

Yarn weight is called dtex and varies according to the individual yarn shapes produced. Generally, for sport, the dtex will be 12,000, but can increase up to 17,000. Heavier than this weight means increasing the thickness and width of the individual fibres, which can be too large for the next stage in production – tufting.

Keeping consistency in yarn weight is essential for the end product to match test results and product specifications.

Twisting or wrapping?

When fibres are extruded they are either wrapped or twisted, to enable the tufting process to follow. Twisting is considered better as it is much easier for the rest of the production process, but wrapping is quicker at the extrusion stage of the process. Both methods are acceptable in the end product.

Texturised yarn

When yarn is produced for hockey, a curl is added during the extrusion process. A lighter yarn is used, normally around 8,000 dtex, twisted then heat set to create a permanent crinkle. The curl can be added in an “in line” process, or, more commonly, a second stage is required, where the yarn is texturised on a different machine. Both ways produce consistent curls, the extent of which can be controlled during the process. “In line” is faster and more cost effective.

Specialist supplier or “in house” production?

There are specialist companies that produce yarn and sell to smaller turf producers. This allows tufting companies to buy at the most competitive price, or choose the shapes of yarn they wish. However, the influence of yarn producers is such, that often they will dictate to a turf producer what yarn to use, and this can add a hefty margin to the end cost. There is also a huge guessing game when it comes to what yarn a tufting company needs to hold in stock, which can create supply line issues or require huge storage facilities to hold yarn, “just in case”.

In contrast, producers with their own extrusion capabilities have much more freedom to design unique yarns, manage the cost better and be in full control over its own stock. “Just in time” production is also possible, with costs kept down through a much reduced need to hold stock yarn.

Warranties

Most monofilaments carry at least a 5-year warranty. Those made from C8 polymer offer a longer warranty period, up to 12 years, depending on usage. In hot countries, where UV degradation is an issue, the warranty periods may reduce, but in northern Europe, the life expectancy of yarn is much greater than the warranty period, although you may see a reduction in colour and a gradual brittleness develop in the yarn, after the warranty period ends.